I'm continuing to document some of the reviews I wrote for AROUND CINCINNATI in 2020, the show's final season. You can still listen to a recording of this review online if you prefer. But here is the script:

Most springs, I spend four days in March with a bunch of writers on the Scuppernong River in North Carolina. Some of us are songwriters, others are true crime novelists, humorists, travel and food columnists, and a couple of the participants make documentaries that air on public television. The retreat leader always gives a morning writing prompt, then we wander off into the small town of Columbia to walk the board walk along the river or to poke our noses into the various shops along the main street. One morning our prompt was a poem entitled “Aubade,” that gave rise to a spirited discussion about why most of us can’t identify morning bird calls. Donna, our resident videographer and purveyor of excellent shrimp and grits, proclaimed that no one should graduate from any school system without knowing how to identify at least a few native bird calls.

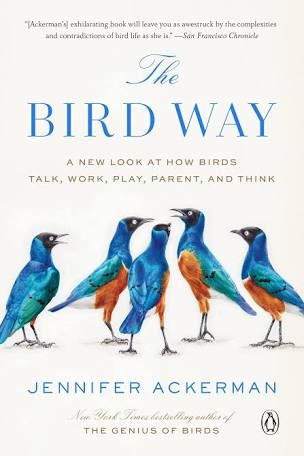

That statement gnawed at me all that morning as I sat down to write a song called “Song of the Dawn,” combining our prompt about aubades(which are morning love songs) with Donna’s passionate declaration that we, as a species, should really know more about the birds that greet us each new day. So, when I had the opportunity to learn more about bird behavior by reading The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think by Jennifer Ackerman from Penguin Press, 2020, I was ready to know more about the wrens, cardinals, woodpeckers, thrushes, finches, swifts, herons, and buzzards that share my world here on the big hill in Wilder, KY. What I learned is both surprising and intriguing.

First off, all that we backyard bird watchers think we know about birds is probably based on a very limited male-influenced research view of the North American bird population. Ackerman busts a few myths right out of the gate. For one thing, I had previously understood that most female birds don’t sing. But according to Ackerman’s research, not only do females sing, they often zero in on their mate’s song so tightly that they answer it with no breathing space in between the notes as if to say, “this one, he’s mine, get your own.” Some mating pairs seem to compose their own “call and response” song to signal their close bond to any interlopers.

Another surprising thing about my backyard birds is that they develop a dialect specific to the dangers of this place. The loud chatter I hear sometimes as I walk out the back door is a cross-species warning about the black snake slithering through the ivy, or the feral cat hanging around the barn, or even a warning that someone has spied the red- tailed hawk soaring over the oaks. And according to Ackerman’s sources, if I walked out of a house five miles from here, the chatter would be specific to whatever dangers the birds face there. I find it amazing that they’ve invented these adaptive warning systems.

While reading this interesting discussion of bird talk and song, I had hoped to learn a few things about the three buzzards that circle our lake each day this spring. Of course, I grew up hearing that they only circle when there’s something dead in the area. I even joke with my husband that they are probably just waiting for us to keel over since we sit still and watch them cruise over the lake, adjusting their wings to take advantage of the wind. Here’s what I learned about the buzzards. First of all, they are not buzzards at all, but actually turkey vultures. And they can’t sing because they don’t have a syrinx—a bird’s voice box. They do make some audible grunts and clicks to communicate, but no song or cry is possible. And while most of us cringe at their eating habits—they do indeed eat dead animals—they have evolved to keep themselves disease free during eating. They have no feathers around their head to trap microorganisms and often pee on their own legs to both cool themselves and/or remove any detritus that might accumulate. So, they clean up roadkill for us, and keep themselves sanitary as well.

Ackerman uses the turkey vultures to illustrate how birds not only see their food, but are also capable of smelling it. Studies support the notion that turkey vultures often home in on the chemical smell of decay. By using mercaptan in their studies—the same chemical that gas companies use in pipelines to make natural gas smell like rotten eggs, researchers were able to test the notion that yes, birds are often quite capable of smell.

The chapters on work examine not only how birds cooperate to achieve their common goals in feeding, nesting, mating and parenting, but how they also compete in such enterprises. One species of bird developed an ingenious method of fire-starting to flush out the insects they needed for food. These birds observed that swarms of insects would rise up from forest and brush fires, so they swooped in to feed whenever they happened on a fire. That in itself would make them seem clever enough, I suppose, but these birds learned that if they picked up burning sticks and set fresh fires, they’d flush out even more bugs to eat. While there have been no controlled studies to test this work behavior in birds, there are many accounts from frustrated firefighters who have observed the birds setting fires behind their just-dug trenches.

Probably my favorite chapter involved how birds play. One species of alpine parrot, called the kea, loves to throw snow balls, ride down slopes on “sleds” constructed or gathered from any nearby debris, remove glasses right off the noses of researchers, and toss traffic cones about the highway just for sport. They even have a “song” or vocalization that means “play time.” Researchers set up one study to test the amount of play behavior that took place when keas heard a recording of their own call. It seems that they heeded that call with increased goofy behavior that had no purpose other than insuring a good time.

The chapters on mating and parenting are sometimes quite graphic. The sedate mallard couples I have admired swimming around our lake have an especially brutal (for the females) mating frenzy. The scope of mating and parenting behavior in birds ranges from couples who mate for life to couples who drop their eggs in a domed nest and leave their young to dig their way out and fend for themselves.

And then there is the cuckoo, who is a parasitic brooder, using the nests of other birds and an evolved mimicry of the hosts’ egg pattern to increase the likelihood of their fledglings’ survival. While some birds— acting as a kindly aunt or uncle—help rear a family member’s fledglings just because they prefer to. And some totally unrelated birds of the same species lay a community of eggs in one nest then raise those fledglings in a kind of bird commune.

But probably the most important thing I’ve learned from reading about bird behavior is that their brains contain tightly compressed masses of brain cells relative to their size, making them extremely adaptive—and in some species like the corvids—capable of higher reasoning than apes. Ackerman muses in her final words that perhaps someday, highly evolved ravens will dig up our human bones and puzzle at us like we do at the dinosaurs. She gives a whole new meaning to the phrase “bird brain.”

JENNIFER ACKERMAN is a New York Times bestselling author who has been writing about science, nature, and human biology for more than three decades. In her extensive bio, I found that her editing experiences with academic presses plus staff writing and researching positions for National Geographic led her to write work that aims to explain and interpret science for a lay audience and to explore the riddle of humanity’s place in the natural world, blending scientific knowledge with imaginative vision. You can find a link to The Bird Way, just released this month, at WVXU.org/ aroundcincinnati. I am Roberta Schultz

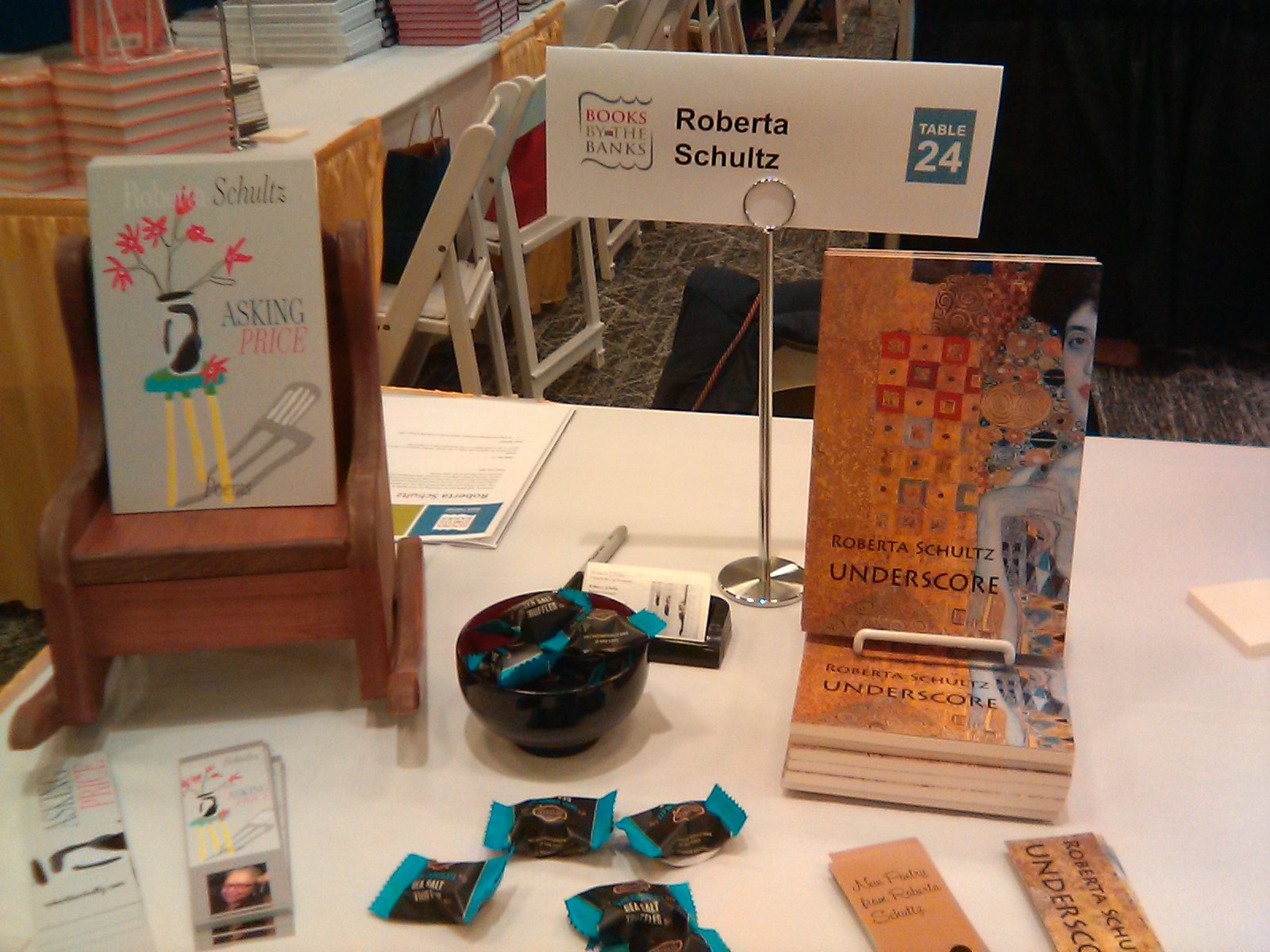

I attended three book festivals this fall with my new chapbook from Workhorse Writers, Asking Price. Writers & Authors Symposium on September 23 in Dayton, OH was a great experience for me even though I was the only poet in attendance. Dayton's main library hosted this well-attended event which included many panels on writing and publishing.

I attended three book festivals this fall with my new chapbook from Workhorse Writers, Asking Price. Writers & Authors Symposium on September 23 in Dayton, OH was a great experience for me even though I was the only poet in attendance. Dayton's main library hosted this well-attended event which included many panels on writing and publishing.