Dr. Nikki Taylor will return to Cincinnati as part of Harriet Beecher Stowe House's lecture series on October 22. You can attend in-person or online by following the "lecture series" link.

Here's the review I did of her book, Driven Toward Madness, for Around Cincinnati. You can read it here, or have a listen.

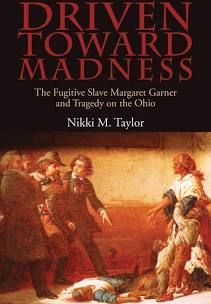

Driven Toward Madness: the Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio

I am Roberta Schultz

Writing a history book about the real woman who killed her own toddler rather than let her be returned to slavery could not have been easy for Dr. Nikki Taylor. I assumed that just writing a review about the subject would be difficult for me. The truth is, I usually dawdle around the middle of most nonfiction works examining the photos and documents displayed there, hoping to avoid actually wading into the chapters themselves. But something unexpected happened when I picked up Driven Toward Madness: the Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio from Ohio University Press. I sat down at the lake in a lawn chair on a freakishly warm day in February and devoured every word in one sitting.

So why is this well-documented history book a page-turner? There is Margaret Garner herself, of course, who inspired such haunting works of fiction as Beloved by Toni Morrison and the inevitable comparison to Greek tragedy in works like Steven Weisenberger’s Modern Medea. But as Dr. Taylor so skillfully points out, Margaret Garner left no diaries or first hand accounts of her escape, capture and desperate decision to slit her daughter’s throat. As a slave—and therefore someone’s property—she was prevented from learning to read and write. And even as one of the few runaways to ever testify at her own fugitive trial, her words do not live on in a trial transcript—as there are no existing official records. Instead, Taylor shapes her rendering of the real Margaret Garner from newspaper accounts of the trial, from hand-written indictment and requisition orders, as well as from the manuscript collection of John Pollard Gaines, Margaret’s original owner. Focusing those scraps of history through the sharper lenses of black feminist theory, trauma studies, genetics, history of emotions, and literary criticism fleshes out a real-life woman in her proper historical and cultural context.

Especially compelling to this Northern Kentuckian, were Taylor’s descriptions of slavery as practiced in Northern Kentucky compared to the hotbed of abolitionist activity across the river in downtown Cincinnati. Nothing in my American or Kentucky history courses prepared me for the brutality of small farm slavery in my own region. I had wrongly believed that the worst separations of families occurred in the deep South on large cotton plantations and not in a neutral state like Kentucky. I had also assumed that to be a slave on a small farm might be an easier life for the enslaved. Taylor’s descriptions, based largely on manuscripts left by the slave owners themselves, paint darker scenarios where slave families were worked very hard and divided between local landowners located miles apart. This separation resulted in the families seeing each other rarely, forcing them to hold their blood ties together by sheer determination. It was such determination—and the fact that freedom beckoned from just 16 miles away— that led Garner’s family to dream of escape.

Three of the most interesting accounts in Driven Toward Madness include the actual details of the Garners’ perilous “dead of winter” escape from the Richwood farm where Margaret Garner was enslaved to a 6th Street Underground Railroad location in Cincinnati, an account of the defense attorney, John Jolliffe’s fascinating use of contemporary laws to defend Robert Garner’s family in court, and interviews that Reverend Horace Bushnell—a minister active in antislavery pursuits—and abolitionist, Lucy Stone conducted with the imprisoned Margaret Garner. These interviews, while filtered though the sensibilities of each interviewer, seem to bear the only witness to Margaret Garner’s explanation for killing her child.

This excerpt from a question and answer exchange between Garner and Rev. Bushnell speaks to Garner’s desperate decision:

“Q: ‘Margaret, why did you kill your child?’

A: “It was my own,’ she said; ‘given me of God, to do the best a mother could do in its behalf. I have done the best I could! I would have done more and better for the rest. I know it was better to go home to God than back to slavery.’”

_____________________________

I plan to join the lecture online. It proves to be another compelling experience.